Practice: The Heart of Our Lineage

by Patricia Walden

Sadhana

“Surely I have said, asanas are my prayers. Now I say practice is my mantra. Practice, practice, practice makes the intelligence to be humble.”

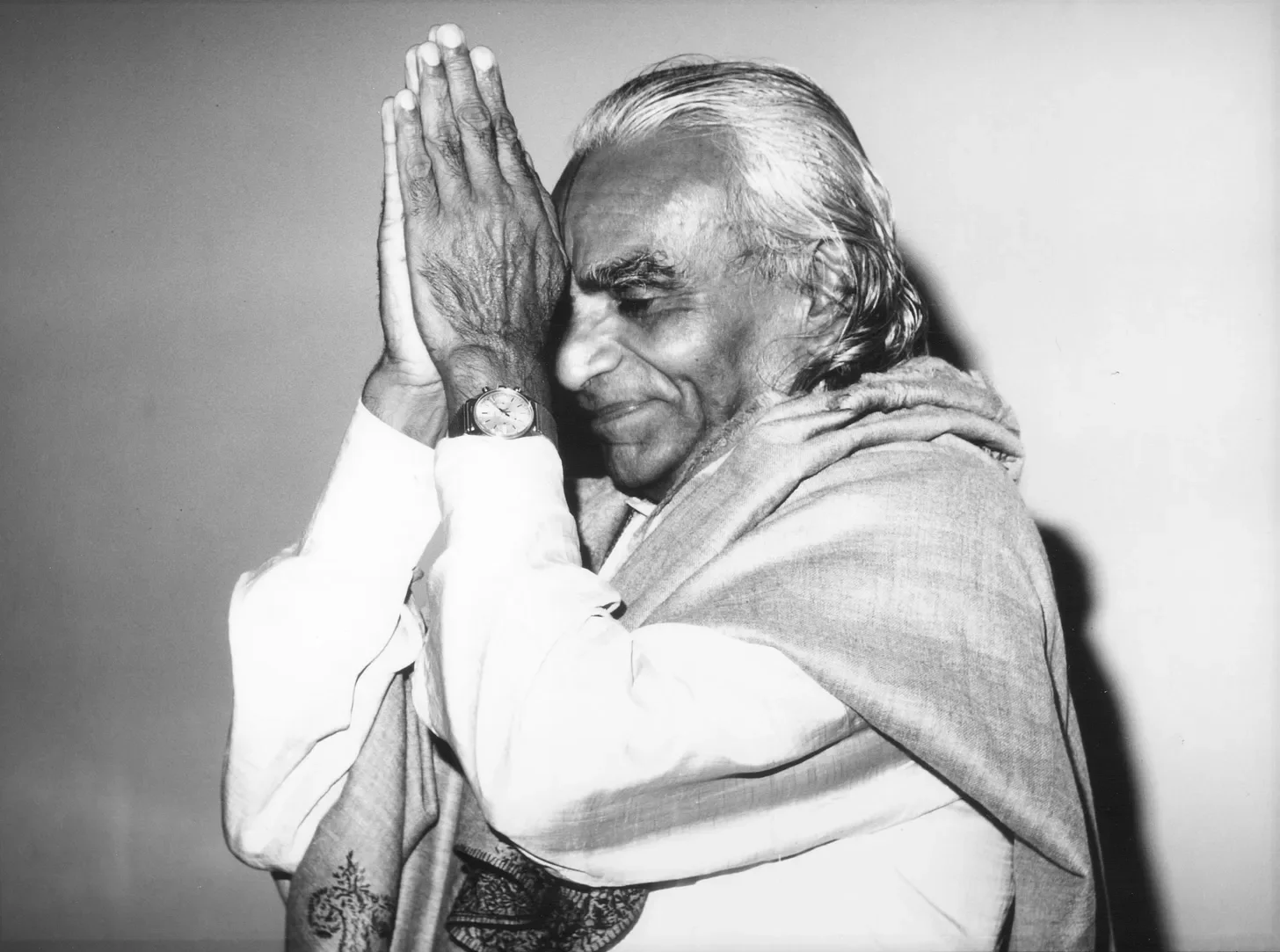

Our lineage is based on sadhana. Guruji devoted his life to the practice and study of asana, pranayama, and yoga philosophy. Because of his practice, he achieved remarkable things. He showed us what is possible when one dedicates oneself to the practice of yoga. There was a palpable energy about him that was the result of his daily practices. Many of us felt that electricity the first time we met him in person. His determination to share yoga with the world brought him to us, but the fire of his practice is what drew us to him and kindled in us the desire to be close to him. Guruji’s practice ignited us. We saw what he was capable of, and this gave us an inkling of what we might be capable of, if only we could commit ourselves to practice with the same uncompromising zeal.

While practice was the constant in Guruji’s life, we also saw the changes in his practice over time, and we saw how Guruji himself changed. In the early days of the Institute, he used to give three-week intensives. We would come early before class and watch Guruji practice pose after pose after pose. The speed and intensity of his practice was mirrored in his teaching of us. He yelled, he shouted, and he cajoled. After many a class, we would sit on the bench outside the Institute and wonder if our legs would be able to carry us back to our hotel rooms. We felt wrung out and exhausted—and we loved every minute of it and couldn’t wait to come back the next day.

Over the years, Guruji’s teaching changed: He taught us fewer poses in a class but lead us to penetrate them with greater refinement and sensitivity. As he used to tell us, “When I was young, I played; now, I stay.” Whereas our first impressions of Guruji when we met him were of his fiery nature, over time, the fire was transformed into luminosity. He was aiming for the soul, and over the years, we could see that his practices had led him to a deep connection with the inner divinity. We saw how Guruji could become completely and totally absorbed in a pose, where the body and the breath became absolutely still, and where a single moment could stretch into infinity. In Guruji, we saw that it was possible to live each moment in a state of Yoga.

BKS Iyengar in supported urdhva dhanurasana

Guruji was an extraordinary being: a sadhaka who was transformed through yoga. I now know that this is one of the greatest blessings in my life—that I had a guru who evolved. When your teacher transforms, he brings you along with him. As he went deeper into his embodiment, he showed us that transformation is possible through long, uninterrupted, and dedicated practice. In trying to emulate his dedication to practice, he showed me that I was capable of more than I believed possible. When you think you can’t do something but then you do it, this truly does change your life. Because of his presence, I was motivated and able to break through the voice that says, “You can’t.” That gave me the confidence and the inspiration to work this way on my own. Because Guruji changed over time, he showed me that I could also change over time.

As students in Guruji’s lineage, how do we help ourselves achieve our potential? How can we draw on his example to inspire ourselves to practice wholeheartedly, with faith, courage, and absorption? In this article, I want to share some of what I have learned about practice over the past 35 years in the hope that it can help shed a fresh light on your practice so that you might see how it can evolve over time.

In the Core of the Yoga Sutra, Guruji tells us that the effect of yoga depends on one’s motivations. In the beginning, our motivations are often very practical and oriented toward the body: to become stronger, to become more flexible, to lose weight, to become healthier. We might also want to calm down, reduce anxiety, or escape a brooding mind. That we begin with these kinds of motivations is not a bad thing. Our desire to “get something out of our yoga practice” can provide the initial impetus to practice when we are first struggling with willpower. We may also have motivations that run deeper than simply physical or mental health. Many of us who started yoga in the 1960s and 1970s were motivated by a desire for enlightenment, although to be honest, we didn’t really know exactly what that was. But we had a sense that there was a reality beyond our day-to-day identification with like and dislike, success and failure, and that hunger for something more drove us to approach yoga as a spiritual practice. It is worth recognizing that this desire for self-realization exists in all of us, even if it is buried.

Over time, our motivations change as we change. Or it might be more accurate to say, our motivations clarify as we become clearer through our practice. We find that the things we need to be happy in life change as we move from the external (bahiranga) to the internal (antaranga) to the innermost (antaratma).

This is to say, if you’re not getting what you want out of your practice, look to your motivations. Learn to study not just how you practice but why you practice. By studying our motivations, we can bring an intentionality our yoga practice. This is skill in action and is one of the things that distinguishes the intense practitioner from the casual practitioner. While in the beginning, it is normal for our motivations for practicing yoga to be mundane, through tapas (burning zeal in practice), svadhyaya (self-study), and isvara pranidhana (surrender to God)—what Guruji calls sadhana krama (sequential progression in practice)—practice purifies us so that our tamasic and rajasic qualities are controlled and sattva becomes predominant in our nature. As a result, our motivations evolve so that they take us in the direction of abiding joy (sreyas) rather than transient pleasure (preyas).

Tapas

““Tapas is nothing less than determined effort in sadhana.””

Establishing a yoga practice in the beginning requires willpower. By “yoga practice,” I mean asana practice, as this is where most students begin, even though Patanjali tells us that yama and niyama should come first and asana should progress to pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi. But as Guruji shows us, the body is our first instrument and practicing asana with zeal and determination helps us break through our tamasic (dull) nature. By willpower, I mean, in Guruji’s words, “willingness to do.”

In the beginning, willingness to do is intermittent. You go to class, and you feel totally inspired; you feel like you’ve really done something. But then you go home, and the fire is not there. Students tell me they love yoga and they feel the benefits of practice, but they have a hard time actually doing it at home. Why does this happen? Is it laziness? Is it the challenge of being alone with yourself in silence? What my students often tell me is that they don’t know what to practice. They’re used to doing asana with a teacher in class telling them what to do, but it is more challenging when they are alone and they don’t have the energy of the group to carry them along. In addition to the practical matter of what poses to practice and how to do them, we need to develop our power of concentration. This takes time.

These days it is possible for a yoga student to take many classes a week, so much so that one can easily avoid practicing at home by oneself. While certainly it is better to attend class than not to practice at all, please understand that to become firmly established in yoga, you must develop your own personal practice. There are things that come to you on your own mat, when you are absorbed in your own embodiment, that do not come when you are in a class and your mind is externalized. For this reason, I encourage my students, when they have passed through the initial “honeymoon” phase of attending many classes a week, to settle on one or two regular classes a week and then invest effort in developing their home practice.

At first we can get caught up in a challenging inner dialogue. “Go and practice.” “No!” “Go and practice!!” “No!!” Sometimes we bargain with ourselves. “Ok, I will go practice, but first let me finish sending these important emails.” “I can’t possibly practice until all of the laundry is folded.” Think about all the energy we waste in bargaining with ourselves, and then consider what it would be like if we could become unconditional about our practice the way Guruji was unconditional. No matter what, he was in the practice hall at the Institute every day for all to see. Even when he was sick, he would practice. Even when he was travelling, he would practice.

Most people brush their teeth before they go to bed and when they get up in the morning. It never occurs to us to say, “Oh, I’m late today, let me not brush my teeth.” If something happens and you have to delay brushing your teeth, it makes you uncomfortable until you’re able to do it. It should be like this with practice. Once you start practicing every day, if there is a day when you can’t practice, you miss it. It takes a while to establish the healthy samskara (impression) of practice, but once you do, it becomes as unconditional as brushing your teeth every morning. The good news is that once you start having success in practicing regularly, that will build your will to practice more. It takes tapas to begin to practice, but tapas builds tapas.

Early on, we need to establish structures in our environment that can help us practice. For example, consider having a space in your home that is dedicated to yoga. For so many years, I watched Guruji practice in the hall at the Institute. To this day, we feel his vibration in that space. When you practice every day in the same space at home, that physical space is devoted to practice. Just as we build the vibration of yoga in our cells, we build a vibration of yoga in our practice space at home. For many years, I watched Guruji come into the practice hall, walk over to the rope wall, put his timer down, take his dhoti off, go to the wall and do 10 minutes Adho Mukha Svanasana. That was his daily ritual. To see that consistency every day was priceless.

When I lived in a very small apartment, I would practice in my living room. Every morning I had to move plants out of the way and push the couch back. After a while, I just left the things that way so there wasn’t a lot to do to prepare for practice, everything was set out. When your mat is set out, when your blankets are there, your practice is there waiting for you.

In those early days, the moving of furniture and plants, having tea, and starting my practice was a ritual for me. Nowadays, a typical day for me begins in very much the same way: I begin by studying the Yoga Sutra or some text that relates to yoga philosophy for a half an hour. I chant the invocations—the Patanjali slokas and the Guru Stotram—and then I begin my pranayama practice. After pranayamaand Savasana, I sit a short time to experience my state of mind. And then I begin my asana practice, which I don’t finish until I’m done. This has become my daily ritual now after 35 years. Yoga practice is the thread that connects all the days of my life.

I tell my beginning students, first make a commitment to yourself to practice three times a week. It doesn’t need to be a long time—15–30 minutes of concentrated practice for a beginner can be a lot and is more effective than two hours of distracted practice. The important thing is to do it consistently, preferably at the same time each day. Of course, most yoga practitioners are householders, and it can be challenging to carve out a regular time to practice with competing commitments to family and work. Guruji himself talked about being a householder and practicing. As a young bachelor, he would do asana while waiting for the rice to cook. Later, as a family man, he would have to do his own practice after bicycling all over Pune to teach. The most important thing, though, was that he continued to practice throughout.

Sometimes, a short practice done with focused awareness can be more powerful than a long practice with no discernable end in sight. The most important thing, as Geetaji says, is “to make time for practice and to make yourself available for that time.”

There are times we can have a spontaneous desire to practice. As a young practitioner, I was walking in Harvard Square one afternoon. I had been working on dropping back to Viparita Dandasana from Sirsasana in my practice and had not been successful. Suddenly I had this urge. I thought, “I can do it!” I ran back home and tried it three times, and on the third attempt, I got it. It was an urge I had. I thought, “Now I can do it!” and I did it. We should recognize these spontaneous urges to practice as the yogic samskara getting activated in us. When this happens, we should do our best to nurture these impulses. As the yogic samskara gets stronger and stronger, the tamasic samskaras will weaken until practice becomes a way of life for us.

In the beginning, it is helpful to practice what you remember from class. Take some time to jot down notes on the sequence and the points taught after class so that you can practice these at home. These days, there are many books available with practice sequences, but when I was a young practitioner, most of these resources did not yet exist. I practiced the sequences that I learned from Guruji in Pune. After class, my colleagues and I would go to lunch and try to remember everything we had been taught. As soon as we left the gates of the Institute, we would be talking about what Guruji taught us. We were filled with excitement and wanted to write our notes right away before we forgot. To this day, I still practice some of those sequences.

When I returned from those trips, I had to learn how to structure my own practice at home. Early on, I would give myself poses to work on. One of the most difficult poses for me in the beginning was Halasana. I would get a tremendous burning sensation in the kidneys. I made a commitment to myself that every day I was going to practice Halasana, starting with three minutes and working up to five. That was my first introduction to tapas at home. Over time, I also realized that, in order to make progress, I had to make a commitment to practicing all of the families of poses on a regular basis, not just the poses that I liked. By watching Guruji, I learned to set myself a schedule of practicing all the major families of poses over the course of a week and to adhere to this schedule with discipline.

In addition to the regularity of a weekly practice schedule, I also learned how to make long-term plans for my practice. Once I went for a drive with Dona Holleman and my friend Victor Oppenheimer in Italy. In the car, Dona was busy writing something in a notebook. I asked her what she was working on, and she said, “I’m outlining my practice for the next year.” Then she showed me the poses she was going to focus on. For someone like me, who didn’t have such a structured life at the time, that was a revelation.

If you want to take on a particular pose to improve, here are some ways to approach the process. First, study the shape of the pose. Where did preparation for this pose begin? What are the needed actions of the different parts of the body, and where were these actions first taught? For example, consider the geometry of Urdhva Dhanurasana. We can see that we need mobility in the armpits and groins and strength in the legs. Consider how Virbhadrasana Iprepares the legs (especially the back leg with the extension of the hip) and the armpits and spine. Observe how Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, Dhanurasana, and Ustrasana continue to prepare the spine for backward extension, while poses like Adho Mukha Vrksasana and Pincha Mayurasana help to strengthen the arms and shoulders and to open the armpits. By practicing these poses over time, we are preparing for Urdhva Dhanurasana even if we don’t realize it. We need hamstring strength so we can create room for the whole spine to extend. All of the standing poses teach this coordination so that the spine receives the action of the arms and the legs. In turn, Urdhva Dhanurasana is the doorway into the advanced backbends, so while we might take on Urdhva Dhanurasana in the short term, in the long term, we aim at Viparita Dandasana, Kapotasana, and so on. There is tremendous richness in organizing one’s practice around short- and long-term aspirations.

The effect that making a commitment to an aspiration and following through has on the psychological body is profound. This is often how I’ve organized my asana practice—to take on something that is difficult and then put sustained effort into pursuing that goal. I didn’t always know if I would reach it or how I would feel, but almost always the effect was positive and transformative. By doing this, we penetrate into parts of our embodiment that we haven’t before. This kind of tapas teaches us to go beyond the limits of our mind and, as Guruji says in Light on Life, “transcend fear, attachment, and pettiness.”

Patricia Walden in eka pada raja kapotasana IV

Svadyaya

As tapas becomes firmly established in our practice, motivated initially by our desire to master the asanas, we quickly find that to make sustained progress, we must also develop discriminating discernment. It is not enough to take what we are taught in class and practice it blindly at home. We have to figure out how much of which actions are needed for our own particular body at this moment in time. We have to develop an understanding of the tendencies in our own body and mind and how to apply the techniques of asana to bring about a state of equipoise and integrated awareness. This kind of self-study (svadhyaya) is the heart of the Iyengar Yoga method.

For example, when I started practicing Urdhva Dhanurasana, my initial motivation was that I wanted my pose to look like Guruji’s pose. I was inspired by the beauty of Guruji’s Urdhva Dhanurasana. But when I tried to do Urdhva Dhanurasana, after 30 seconds, my thighs would be burning. Just straightening my arms and lifting my legs was tremendous work. People think that backbends always came easily to me, but in reality, poses like Urdhva Dhanurasana and Viparita Dandasana were challenging for a long time. Being loose, I had to develop strength and power in my arms and legs so I could support the coiling of the whole spine instead of just bending in half at the lumbar.

The process of self-study in the asanas teaches us to use our effort skillfully. Ultimately, we have to understand over time what parts of the body need to work hard and what parts need to have ease. In particular, Guruji would tell us, “Don’t harden everywhere, including the brain!” In the early stages of practice, we tend to harden everywhere, especially the brain. Instead, Guruji would admonish us, “Don’t use your brain! Awaken the brain of the armpit! Awaken the brain of the chest!” One of Guruji’s main teachings was to get us to awaken the innate intelligence of the body and to use that intelligence to do the asana, rather than using the intellectual brain.

To work in this way requires us to balance attention and awareness. As Guruji taught, attention is one-pointed: We use attention when we bring our mind to focus on one part of the body. Awareness, however, is all-pointed. When we experience the messages the body sends to us in response to an action we have taken, that is awareness.

In Light on the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, Guruji tells us that in asana, we start with trial and error. “As we progress, trial and error decreases and correct perception increases. … Discriminating experiment awakens consciousness. Awareness, with discrimination and memory, breaks down bad habits, which are repeated actions based on wrong perception, and replaces them with their opposite.”

Approaching our daily practice in this way keeps it from being mechanical. Rather than relying on past memories of yesterday’s pose, we approach the poses each day with a fresh mind. For me, the essence of practicing this way is to question, “What happens when I bring my attention to this place in the body? What happens when I perform an action here? How far can I trace the effects of that action?” By asking the question, I begin the process of internalizing the mind.

For example, let’s say I’m doing Tadasana-Samasthiti. First, I bring my attention to the mound of the big toe and the inner heel. I press them down. As a result, I become aware of the whole foot. Maintaining those actions, I become aware of my shins, which at first feel watery. As a result of this perception, I turn the inner calves out and suck the outer shins in, and this makes me aware of the firmness of my inner knees as the sense of wateriness is replaced by a sense of sharpness. I feel the sharp line from the inner knee to the perineum and realize that I can draw the energy of my legs up to meet the torso. My mind is penetrating inward. I travel up and see how far those actions reach into the trunk. I make sure that the side walls of the armpit chest are lifted, and the shoulders and shoulder blades are properly adjusted, and as a result, I feel the life force filling the chest. As I make these adjustments, I trace how one thing leads to another. As the actions come together and are integrated, I have an overall feeling of the pose. I go beyond the experience of individual parts.

When you work this way in any pose, do you feel the mind penetrating inward as you progress from part to part? Does the quality of the mind itself change in that inward-going process? When you are aware, your mind is totally in the present. Awareness opens the mind and expands it so that the mind gets purified and transformed. In my experience, when I practice wholeheartedly with this kind of inner inquiry, I experience a sense of inner vastness that comes from consciousness spreading and expanding without limitation.

This realization—that consciousness can be purified through the process of bringing the body and mind into alignment—was Guruji’s unique contribution to yoga. He saw that asana could be a means to transform a vyutthana citta (outgoing mind) to a nirodha citta(restrained mind)—doing what he used to call a “U-turn.” As we cultivate and culture our discriminating awareness in practice, it is inevitable that our motivations for practice will change. “Doing” the asana for the sake of the asana is no longer enough: We are drawn to study ourselves in the asana in order to reach the consciousness.

Isvara Pranidhana

The essence of svadhyaya is inner listening. As we listen to the messages that the body sends us and adjust so that the intelligence spreads evenly throughout, consciousness changes. Whereas in the beginning, the body speaks loudly and calls our attention from this sensation to that sensation, as we adjust more skillfully, what we hear more and more through our faculty of inner listening is inner silence. In silence, we become absorbed in the infinite being within.

What happens to our motivations when we have tasted this inner peace? In the beginning, we acknowledged that we might start our practice motivated by what our practice can do for us. We practice because we want to get something, whether that is physical ability or mental peace. But what happens to egoistic desires when we have truly purified ourselves?

Geetaji once asked us to consider, when Guruji practiced 108 Tadasana-Urdhva Dhanurasana drop-backs, what was his motivation? Was he practicing Tadasana-Urdhva Dhanurasana to get better at backbending? Was he using it as a “get-fit regimen?” No. Guruji’s practice, she told us, was his upasana. He was practicing as an act of devotion. He was offering his tapas at the feet of the Lord.

What does it mean for us to practice as an act of spiritual devotion? At some point, we no longer practice to get something. Over time our selfish motivations change until practice becomes motiveless. Devotion doesn’t happen because your pose is perfect. It’s the result of years of practice, of learning to internalize your consciousness: It comes from supreme nonattachment. It comes from understanding the spaces between action. As Prashant has said, yogāsana begins when the actions stop.

In Light on Life, Guruji tells us, “When you do the asana correctly, the Self opens by itself; this is divine yoga. Here the Self is doing the asana, not the body or brain. ... It is when the rivers of the mind and the body get submerged in the sea of the core that the spiritual discipline commences.” This aspect of practice is not something that we can force, Guruji says. Practice becomes devotional when we are able to be absorbed in inner silence.

When we practice this way over a long period of time, our relationship to the body changes. As we mature in our practice, we begin to treat the body with reverence. We see it as a sacred vehicle. As Guruji said at one intensive, we begin to treat each part of the body as a precious jewel. This is not the same as having attachment to the body. Rather, we come to understand that as we age, the body will inevitably change. Things that might have been easy for us when we were young may become more challenging as we age. Recognizing the transience of the body is what makes it precious and leads us to treat it as sacred. We develop tremendous gratitude for what our body can do for us in this moment. Our mind transforms when we have this kind of relationship to our embodiment.

If you want to explore how silence can lead you toward this experience of divine yoga, consider how you approach the practice of Savasana and pranayama. Often beginning students don’t practice Savasana at home, but it is one of the most important poses for us to do every day. Guruji often said that “Savasana is halfway to samadhi.” Savasana is a process of shedding, like a snake shedding its skin. In Savasana, we shed the many layers of thoughts, preconceptions, desires, and fears that make up our surface identity. We cut the threads that bind us so that “neither past nor future impinge or taint the present.” We go beyond chronological and psychological time and become absorbed in the present.

When we become able to dwell in the inner silence of Savasana, pranayama becomes possible. In this way, Savasana is not an end, but a beginning. Through pranayama, we refine our inner focus, as we have to use our subtle mind to adjust. Whereas asana starts with the outer mind, pranayama takes us into a deeper sheath. Guruji tells us that in order to do pranayama, we must “understand the art of surrendering the intelligence and willpower from the seat of the head toward the seat of the heart.” In this way, pranayama is the path of devotion.

These days, I almost always practice pranayama before asana, and over the years I have noticed that the mind I bring to my asanapractice is more internal when I practice with this kind of sequencing. As a result, I approach asana from a more internal place. It affects the kind of effort I use and my sensitivity. When I work this way, my practice happens not from the willpower of the brain, but from the grace that flows from the seat of the heart. For practitioners with an established pranayama practice, I encourage you to practice this way to bring a deeper dimension to your sadhana.

Guruji showed us that the practice of a lifetime is a journey from the periphery to the core. We begin with the body—our first instrument—but we should not remain stuck on the outer sheath forever. Self-study in asana and pranayama is a process of involution that enables us to penetrate through the layers of our being, integrating us so that consciousness spreads from the inner layer of the skin to the seat of the soul.

BKS Iyengar and Patricia Walden

As I reflect on my own life of practice, I see how practicing following Guruji’s example has changed me. When I am fully absorbed in an asana, when I surrender the in-breath to the out-breath, when I am silent in Savasana, when my mind is clear, I feel peace in my heart. I feel fullness within and fullness without, and this reminds me of what it was like to be in the presence of someone who had dedicated his whole life to the practice of yoga. In Guruji’s presence, I felt a love that radiated from his very being. That love pierced through my ego and went right to my heart. My practice keeps that feeling alive in me. It makes me feel tremendous gratitude—gratitude that I have a body with which to practice. Gratitude for having taken human birth. And gratitude to Guruji for showing me the path.